This blogpost is a follow-up of a previous article (part 1/2) discussing the hype about Chinese private launchers. While we previously essentially put emphasis on investment and launch vehicles from an offer standpoint, this second and final post focuses on the demand for launchers, in other words to what extent the small sat market will be able to sustain Chinese launchers.

Market Size and Ecosystem Decoupling

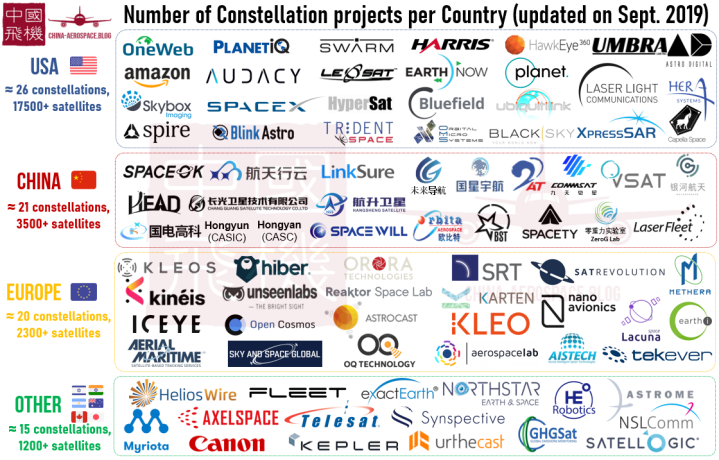

The figure below gives a rough idea of current constellation projects worldwide:

Fig. 1 – number of constellation projects around the world (per country) in Aug. 2019. Based on openly available literature. (credit: China Aerospace Blog)

First observation: there is a rather balanced number of constellation projects in the US, Europe, and other non-Chinese countries (mostly Canada, Australia and Japan). However in terms of number of satellites, the US is clearly ahead with 70%+ of all satellites, due to the massive scale of Starlink, Kuiper (Amazon) and OneWeb. China comes second with 3500+ satellites, roughly the equivalent of constellations from Europe and other remaining countries put together. This is also partly due to the massive scale of the Galaxy Space constellation (900+ satellites).

Can these constellations provide sufficient demand to sustain 10-15 Chinese launch startups ? This, of course, depends on the startups’ ability to get launch contracts from constellation operators, a task that is likely resemble the illustration below :

Fig. 2 – “The Satellite Constellation Tree”, or the difficulty Chinese startups will face to reach launch contracts (credit: China Aerospace Blog)

Ideally for the Chinese, all international constellations would be open to collaboration, which would mean an overall (theoretical) pool of 24500 satellites to target.

More realistically, US constellations are out of bounds for obvious reasons. This already bumps off 17500 satellites due to the sheer size of Starlink, Kuiper, and OneWeb. Probably also hard to reach are government-financed European constellations, which may receive a strong nudge to launch on Arianespace’s Vega rocket. Other foreign players however remain accessible: private European constellations, as well as non-European constellations (excluding the US). This has already been the case in the past, such as with Kepler (Canada) and Satellogic (Argentina) both launching on Long March 11 in 2018. This type of opportunity is more likely to happen once (or if) Chinese private launchers prove their reliability.

Lastly, Chinese constellations are without doubt the low hanging fruit, and the primary targets of Chinese NewSpace launchers.

All in all, this adds up to a market of roughly 5850 potential satellites, a (still) very significant pool.

A more pessimistic market potential would be to imagine that Chinese private launch services would only cater for Chinese constellations. This could happen in the case of repeated failure & reliability issues or political tensions. It could also occur in the case of a strong increase in cost-competitiveness from international launchers. Rocket Lab for example has just announced a reusable Electron launcher to bring costs down, while both SpaceX and Blue Origin are developing ride share programs. In the case of SpaceX, a 50 million USD Falcon 9 launch for up to 60 satellites was put forward, which theoretically could bring costs below the 1 million USD threshold (!), depending on the satellite occupation rate of the launch. And as both players are planning to deploy massive constellations, they are likely to “fill in” any empty spots on each launch. This represents extremely stiff competition for Chinese private launchers, and reusability will be key to hope to match in terms of launch prices.

The marketing of Chinese launchers on international markets, which has so far been unimpressive, could also be another factor. That would leave these startups with a hypothetical 3500 Chinese satellites to launch in the next 4-5 years. Domestic launcher startups may even find hurdles there, since some of the larger Chinese constellations, Hongyun, Xingyun and Hongyan, are SoE sponsored projects, and may decide to launch on the smallsat launchers of the two state-owned giants CASC and CASIC. That leaves the Chinese NewSpace launch vehicles with only a fraction of the intial constellation pie: less than 2000 satellites, and that’s if all Chinese constellation projects make it through to launching. We could even lower these figures further, as several potential Chinese launch clients are from massive constellation operators (Galaxy Space, Hongyan, Lingque, …), which may find ride-sharing on medium-heavy launchers more financially appealing than with the light launchers developed by Chinese private startups. This is why some analysts have hinted at a soon-to-come launcher consolidation.

The Idea of Ecosystem Decoupling

Ecosystem decoupling is a term often heard in the tech sector, where China, with its strong team of home-grown giants (Tencent, Alibaba, Baidu, Bytedance, etc.) relies very little on the global standard: Google, Microsoft, Amazon. Let’s note that this doesn’t stop the Chinese from being innovative nor competitive, as anyone who has been to China would agree.

The Chinese space industry is in quite a similar position. Following the Sino-American dispute in the late 1990s and the setup of the ITAR regulation, China has rarely launched foreign satellites, and launches all its domestic satellites on indigenous vehicles. It hasn’t purchased a foreign satellite since 2010 (Apstar 7B from Thales Alenia Space), and an industry insider mentioned that 95% of all space components used in Chinese space systems were sourced domestically. The internet divide between China and other countries, through the Great Firewall of China, is also likely to spread into space as satellite constellations come of age [2].

Yet, Chinese NewSpace has one of the biggest opportunities to reduce this divide. In the launch market, the strong use of COTS components in smallsats makes ITAR less relevant for Chinese launch vehicles. Similarly, constellations, may they be Chinese or foreign, cover the world by definition and will be needing landing rights in both places, another opportunity for cross-border cooperation. The private nature of (some) Chinese NewSpace startups will incite them to find more market opportunities abroad, while being supported by tech VCs which have experience in the scaling of startups.

Regarding launchers, their success now depends on the ability to make their rockets mission-proven, reliable, competitive, step up their marketing to international standards, and hope for continuous government support as well as a stable international political environment.

Another interesting and complementary read on smallsat launchers is the interview with Firefly, Relativity Space, Rocket Lab, Vector Launch and Virgin Orbit by Greg Autry [3].

References

[1] APT Orders Backup Satellite from Thales Alenia Space, SpaceNews, April 30 2010

[2] The Great Firewall from Low Earth Orbit, Blaine Curcio, WestEastSpace, June 17 2019

[3] Is Space Launch Overheating? I Ask Five Rocket Startups, Greg Autry, Forbes, May 21 2019